Last updated:

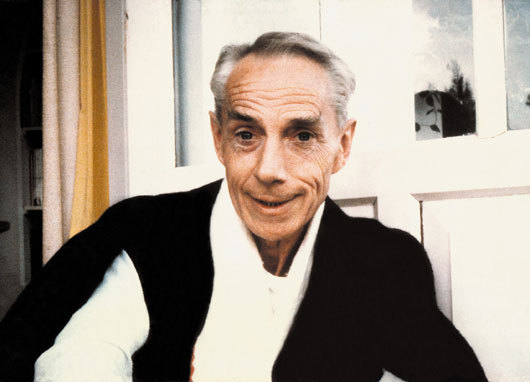

Remembering Hu Hsu

In September 2017, the Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Luo Zhaohui visited Auroville and the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. Addressing a gathering at the 68th anniversary celebrations of the People’s Republic of China at New Delhi soon after his visits, Ambassador Zhaohui remembered Hu Hsu.

“Last week, I visited Pondicherry. It is one of my dreaming places. One of my teachers, Professor Xu Fancheng lived in the Sri Aurobindo Ashram from 1945 to 1978. He was one of the most famous Chinese scholars, translating the Upanisad, Bhaghawad Gita, and Shakuntala from Sanskrit to Chinese. He also introduced Sri Aurobindo to China. More than 300 paintings of Professor Xu were kept in Sri Aurobindo Ashram. Looking at his legacies, our eyes were full of tears. He was one of the bridges between our two countries ... In the history of bilateral engagement, there have been thousands of prominent persons like Professor Xu, including Xuanzang, Faxian, Bodhidharma and Tagore. We should never forget their contribution and legacies ... Standing on their shoulders, we should do more today....We should turn the old page and start a new chapter...”

Hu Hsu (pronounced Hu Shu) was born on 26th October, 1909, into a wealthy family in Changsha in the southern province of Hunan. His family was respected thanks to one of his ancestors, General Hsu. The Hsu family was successfully engaged in the business of silk. At elementary school, a young Mao Tse-tung was his history teacher. While he lived in the family house, Hu Hsu never had to handle money. Later, when he was given some money for the first time, he confided to Shanta, a friend in the Ashram, that he felt embarrassed and didn’t know how to deal with it.

A thorough classical education in literature and the arts was considered a necessary basis in his family. Lu Hsun, the noted writer and literary reformist, considered to be the founder of modern Chinese literature, became his friend and mentor. Hu Hsu studied History in the noted Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong and, thanks to Lu Hsun’s support, obtained a scholarship to study Fine Art and Philosophy in the prestigious University of Heidelberg in Germany from 1929 to 1932. His first major work was a translation of Nietzsche’s Also sprach Zarathustra.

During the troubled days of the Sino-Japanese war, we do not know much about his whereabouts in China, but in 1945, just after the war ended, he decided to head towards the West, that is, towards India. He settled in Visva Bharati in Santiniketan to further his study of Sanskrit (he would go on to translate some works of the great classical poet Kalidasa from Sanskrit into Chinese), and teach the History of Chinese Buddhism at ‘Cheena Bhavan’, the Chinese study centre co-founded in 1937 by Rabindranath Tagore and Tan Yun-shan (who also visited the Ashram, met The Mother, and had the darshan of Sri Aurobindo in 1939). Tan Yun-shan once wrote, “...As in the past China was spiritually conquered by a great Indian, so in the future too she would be conquered by another great Indian, Sri Aurobindo, the Maha-Yogi who is the bringer of that light which will chase away the darkness that envelops the world to-day.” It is probably here that Hu Hsu first heard of Sri Aurobindo.

In Pondicherry

In 1951, Hu Hsu came to Pondicherry. Shortly after his arrival he wrote a poem which sheds some light on his first experiences (translated):

The Mother bestowed a flower for its blossom

Other than offering a flower to the Mother, living in South India nothing else matters.

Flower blossom, flower beautiful, flower can be divine, the divine itself silent, and the flower itself spring.

Time flies, experience beyond the material is new, timeless divine knowledge is ever fresh.

This flower, this leaf, the essence of the present moment, this is the way to realization.

The Mother saw his

potential – not only was he a scholar and master of many languages, but he also

had the desire to translate Sri Aurobindo’s and Mother’s books into Chinese.

Eventually he was given the Villa Orphelia to stay in, a large colonial mansion

with a large garden in the French town, on Rue Dumas, right next to the Ashram

Nursing Home today. He was working tremendously hard, fourteen hours a day.

Manuscripts were quickly piling up, as well as brush paintings. Mother had

brought back from Japan some calligraphy material and She gave some to Hu Hsu

so he could continue to paint. When, in 1967, he exhibited his paintings in the

Exhibition Hall of the Ashram, The Mother wrote a very special introduction:

“Here are the paintings of a scholar who is at once an artist and a yogi,

exhibited with my blessings.”

In a conversation

dated October 30, 1962[1],

she praised him as being a genius who was in fact coining new Chinese words to

better translate Sri Aurobindo. She spoke highly of his translations and

referred to one of his letters in which Hu Hsu wrote to a friend, “If you want

to experience Taoism, come to live in the Ashram, you will have the REALISATION

of Lao-Tseu’s philosophy.” The Mother added: “This man is a sage.”

Chinese Section at the Ashram School

In 1954, Nandlal

Patel had just shifted his business from Pondicherry to Hong Kong. There he

worked to start the Sri Aurobindo Philosophical Circle of Hong Kong, for which

the Mother gave the message: “Let the eternal Light dawn on the eastern

horizon.”

While in Hong

Kong, Nandlal received a letter from Jayantilal (in-charge of the Ashram

Archives) telling him that Mother wanted him to buy a Chinese printing press

and have it shipped to Pondicherry. The Mother added that a compositor should

also be recruited as Hu Hsu could not do the printing work himself. So an ad

was sent to a newspaper looking for a young assistant willing to go to India.

17 applicants replied, and Mother chose a young man from the list named Kau Tam

Sing to come and help Hu Hsu. Nandlal Patel recalls:

Hu Hsu had just

written to him, “This is the Divine’s work”, and Kau Tam Sing was ready, not

asking the questions any ordinary person would have asked…A house was rented

where Hu Hsu and Kau Tam Sing would stay. Hu Hsu used to get up to check that

Kau Tam Sing was sleeping well, he cared for his wellbeing as if he were his

son.”

And so the Chinese

Section of the Sri Aurobindo Centre of Education was born, with the blessings

of the Mother. Hu Hsu single-handedly translated twenty books in twenty-eight

years, including The Life Divine, The Synthesis of Yoga, The Human Cycle, the

Upanishads, On Education, among many others. He also wrote a few original

pieces on the true meaning of Confucianism, and on the origins and deeper

meaning of Chinese characters, thus showing a rare mastery of Indian as well as

Chinese culture and spirituality. All the books he printed stated that they

were “…dedicated to THE DIVINE MOTHER to WHOM the writer remains in permanent

gratitude as it is only with HER boundless Compassion and Grace that this book

has come into being”.

In the Ashram: a friend and a teacher

In his house on

Rue Dumas, Hu Hsu would often welcome his friends. He would also visit his

neighbours, Ange and Peter Steiger. They remember Hu Hsu’s affability and

kindness and the fact that he spoke very good German, much better than his

English it seems, which was rather hard to understand! He once shared with

Peter a breathing technique he was using: inhale and welcome what you want, and

exhale and reject what you don’t want!

Ange, 4 years old

at the time, loved him dearly and still remembers fondly how he would greet his

neighbours’ children when they ran into his study room, showing them his many

brushes and other painting material. This man who worked tirelessly never

seemed to be annoyed by their visits. A few children of the Ashram would also

learn the art of Chinese painting under his guidance.

Hu Hsu loved to

play the Chinese game of Go (called ‘wei chi’ in Chinese) and aspiring players

like Vijay, Roy Chvat, Gary Miller, Steve Phillips, Ingo and Gerhardt Stettner

used to meet in his house every week. Roy still carries on the legacy of Go in

Auroville.

Hu Hsu was also a

regular walker and cyclist, and every Sunday with Pierre Legrand or Peter, he

used to throw divination sticks to determine whether they would go cycling or

walking, and for deciding on the direction in which they should proceed.

Pondicherry then was a walkers’ and cyclists’ paradise! They would visit

Auroville, or the canyons near Utility. Once after a long walk, he explained

how to restore one’s energy levels: “…concentrate the consciousness in the

feet, or gaze at the emerald green of a paddy field.”

Sybille Hablik in

her book 30 Years in India writes about him:

“He was tall and

slender but strongly built. We often saw him, dressed in Indian white pajamas

and riding a bicycle, wearing a green eye-shade….Hu Hsu invited us to join him

on Chinese New Year’s day. We found him in his roomy colonial house sitting at

a two-metre long table with a black glass top. We offered him a flat covered

basket of fruits and wished him a Happy New Year. He had promised to paint

something for me, so before our very eyes bamboos were magicked onto a big

sheet of paper. I held my breath as I followed the movements of his huge brush:

one stroke – the stem; a small diagonal curve – the growth node; another

vertical stroke – the bamboo is growing; a thin line and a few points: there

are four narrow pointed leaves.

With silent

attention we followed the light, sure movements of the ink-brush – we were

experiencing perfect skill.

Hu Hsu led us to

two cupboards that contained the whole of Chinese history in the form of many

individual books. ‘This,’ he said, ‘is an official edition of which only three

copies exist. This is one of them, the other two are in my homeland’.

A melancholy

shadow fell on the three of us at last, as Hu Hsu played patriotic Chinese

marches to us on his gramophone. It was a memorable meeting and for me, it was

the beginning of a lasting friendship.

Today, the rare

books on Chinese history are still preciously kept in a cupboard in the Ashram

Library.”

Auroville

On the day of the

foundation ceremony, the Auroville Charter was read out in the four languages

of Auroville (French, Tamil, English and Sanskrit), and then in Chinese and

Arabic. Hu Hsu translated the Charter, and the son of a Chinese dentist based

in Madras read the Chinese text. The earth from both the Republic of China

(Taiwan) and from the People’s Republic of China (Mainland) were poured into

the urn by Ashram youth (Kanu Dey and Vimala Sandalingam for Taiwan, and Bokul

Chakravarty and Hema Singh for Mainland China).

In an article in

Nan Yang Siang Pau, a newspaper in Singapore, Hu Hsu introduced the project of

Auroville to the Chinese-speaking world and spoke about building “…a Pavilion

which can represent the culture and arts achievements of the great Chinese

civilisation”, and invited Chinese scholars and artists to participate.

17th November, 1973

Roy recalls an

incident on the fateful night The Mother left her body: “[Hu Hsu] was a very

special kind of person. He once told me he could look at somebody and tell if

he was going to die or not. I said, ‘Oh it’s interesting!’ He said that well,

it wasn’t interesting, because when the Japanese had invaded China, everywhere

he looked he saw people about to die. […]

I used to play Go

with him. On November 17th, in the middle of the game, he stands up and says,

‘Let’s stop playing.’ I looked at the clock: it was 7.25p.m. He says, ‘It would

be good if She could live up to a hundred’.”

Return to China

In 1978, after the

end of the Cultural Revolution, Hu Hsu decided to go back to his homeland. A

young man from Hong Kong, Desmond Hsu (Ramana) arranged his ticket and

travelled with him. In Delhi, he stopped to get his Chinese passport for he had

come to India before the People’s Republic of China had been founded in 1949.

He stopped for a while at Sri Aurobindo Ashram, Delhi Branch. There Hu Hsu

spoke at length with Tara Jauhar and did two paintings for her. She remembers,

“He spent a long hour in conversation with my father and both of them, I

remember, were very emotional. He left

my father’s room and I helped him with his luggage to the taxi as he left for

the airport and China.”

Back in China, he

joined the Institute of World Religions, a department in the well-known Chinese

Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing. Living much the same way as he had lived

in the Ashram – quietly by himself – he remained engrossed in his inner quest.

He continued his study, writing, and painting work, and shared his vast

knowledge and experiences with fellow scholars and students. Soon he became

known as one of the foremost Chinese scholars on Indian culture and

spirituality.

His colleagues saw

a remarkable similarity between him and the legendary Hsüan-tsang, the Chinese

Buddhist monk who travelled to India in the 7th century, lived at Nalanda,

learnt and translated the original Buddhist sutras, and returned to China with

the sacred knowledge of the West (India). The parallel with Hu Hsu’s own life

is striking. His contribution is seen as particularly significant since he translated

and returned to China with new sacred knowledge – the ancient pre-Buddhist

spiritual knowledge of the Upanishads and the Gita, as also the contemporary

spiritual knowledge contained in Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’s writings. After

his return, Hu Hsu came to be known as Hsu Fan-cheng (also written as Xu

Fancheng) – the one purified by the realisation of the Brahman consciousness.

On 6th March,

2000, Hu Hsu left his body.

New Horizons

But his story is

not over. While Hu Hsu’s translations could not be sold in China of the 1970s,

there is a growing interest in his writings today, and through him, in Sri

Aurobindo and The Mother’s philosophy and vision. His students and colleagues

in Beijing brought out his Collected Works in 2006, and the response to them

has been very positive with Universities in China starting to read Sri

Aurobindo’s philosophy, and a few students studying his works, and even the

Integral Yoga, as part of their doctoral theses. Discussions are also underway

to open the first Centre for the study of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother’s

writings in China. A small but growing number of Chinese-speaking seekers also

visit the Ashram and Auroville inspired by the works of Hu Hsu, a few of them

even choosing to settle down.

One can only hope

and pray that the Mother’s message given 55 years ago is indeed starting to

take shape before our eyes, in our own times:

“Let the eternal Light dawn

on the eastern horizon.”

Eric Avril and Devdip Ganguli

It

was published in Auroville Today in

January 2018 (Issue No: 342).

[1] Recorded and published in The

Mother's Agenda, Volume 3, Page 392-393 (1982 first English edition).