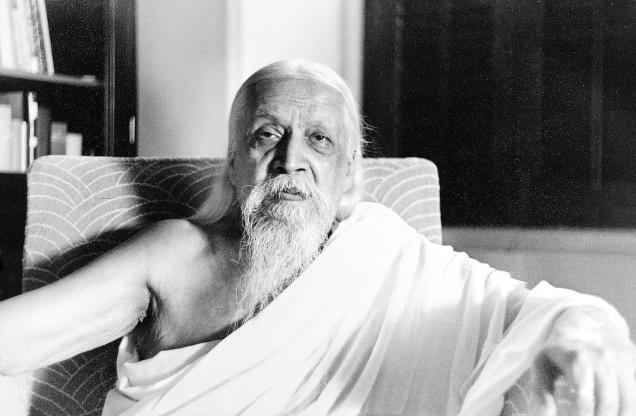

Sri Aurobindo

An edited version of a talk given at the Nehru Centre, London , by Sonia Dyne.

October 2007

No one has ever explored the nature of freedom more profoundly and passionately than Sri Aurobindo. ‘The longing to be free' he wrote ‘is lodged in such a deep layer of the human heart that a thousand arguments are powerless to uproot it'.

Sri Aurobindo looked at the concept of freedom first through the eyes of a revolutionary political leader who was also a poet, and later through the eyes of the mystic and spiritual Master that he became. What does ‘freedom' mean? How can it be realised for the individual and in the collective life of a nation? How do we strike the right balance between individual freedom and the collective interests of a society or nation? Why does the struggle for freedom, fuelled by brave and inspiring words, so often end in bloodshed and a new kind of tyranny?

In the course of a lifetime devoted to finding answers to these questions, he gradually developed an integral vision of human freedom that has become his legacy to India , and through India , to the world. For him, freedom was more than just ‘a convenient elbow room for our natural energies'. For him, freedom was an eternal aspect of the human spirit, as essential to life as breath itself. His whole concept of freedom is based on the premise that there is in mankind an evolving soul requiring freedom for its evolution, just as there is in nature a secret urge towards unity. These twin demands of our nature, acting overtly or behind the scenes, act as a spur to progress until man fulfils his destiny to exceed himself. They must be reconciled if our questions about freedom are to find an answer.

My hope is that I will be able to convey something of that vision and to show how it developed and was enriched in the course of an extraordinary and often turbulent life. Tonight, almost on the eve of India 's National Day, I can think of no more appropriate place to start than by the first part of Sri Aurobindo's message to the new nation, broadcast on All-India Radio 60 years ago:

"August 15th 1947 is the birthday of free India . It marks for her the end of an old era, the beginning of a new age. But we can also make it by our life and acts as a free nation an important date in a new age opening for the whole world, for the political, social, cultural and spiritual future of humanity. August 15th is my own birthday and it is naturally gratifying to me that it should have assumed this vast significance. I take this coincidence, not as a fortuitous accident, but as the sanction and seal of the Divine Force that guides my steps on the work with which I began life, the beginning of its full fruition. Indeed on this day I can watch almost all the world movements which I hoped to see fulfilled in my lifetime, although then they looked like impracticable dreams, arriving at fruition or on their way to achievement. In all these movements free India may well play a large part and take a leading position… ( Ref. 1)

This was a message that looked to the future. The achievement of Independence was only a prelude to India 's future role as a world power – an essential stage in order that the qualities of India 's soul might re-emerge from the sleep of ages and be given to the world. But at the turn of the last century the immediate need was the liberation of India from foreign rule. Nations, like individual men, cannot evolve to their fullest potential as long as the swadharma is not able to express itself freely in the collective life.

From a very young age Sri Aurobindo was a passionate reader. Shelley was a favourite; something of that poet's fervent admiration for the ideals of the French revolution entered deeply into his consciousness. Later he would recount that he read over and over again Shelley's The Revolt of Islam, with its passionate advocacy of freedom as an ideal because something in him responded to it. Even then he had an idea of devoting his life to a similar world movement in defence of freedom. At this time, and during his years at St Paul 's School, he saw the French Revolution through the eyes of the English Romantic poets, and from them first learned the magical formula – Liberty , Equality, Fraternity. That formula would become central to his concept of freedom.

In London , and later at King's College Cambridge, Sri Aurobindo found himself drawn to the nationalist ideals of men like Charles Stuart Parnell in Ireland . One of his early poems in praise of Parnell is significant in the light of what was to come:

Patriots, behold your guerdon! This man found

Erin, his Mother, beaten, chastised, bound,

Naked to imputation poor, denied,

While alien masters held her house of pride…(Ref. 2)

That image of the Mother in chains entered so deeply into his consciousness that it would become a rallying cry to galvanize the youth of India , and unite her citizens in their opposition to British rule.

On February 6th, 1893, Sri Aurobindo returned to India . He was 21 years old and had been away from the land of his birth for 14 years. The second great transitional point in his life was about to begin.

He began by immersing himself in every aspect of Indian life – her culture, her traditions, her religions, her languages (ancient and modern), the aspirations of her people. He taught English and French at the English College in Baroda besides a variety of other duties in the service of the Maharaja. And all the time he continued to write, not only poetry but letters and articles critical of the Indian National Congress for its lack of firmness in dealing with the imperial government. He became increasingly aware that his true mission in life was to work for the Independence of India from British rule and he threw all his energies into the struggle. Through political activity and his editorship of two influential newspapers, his fame and influence grew rapidly.

In his public speeches and writings, Sri Aurobindo began to lay stress on the importance of Independence not only for India 's sake but for humanity as a whole. His concept of freedom had widened to embrace the whole world, and he had come to see clearly the importance of harmonising the claims of freedom with those of equality and brotherhood. Concerning the failure of the revolution in France he wrote:

"It (freedom) is the goal of humanity, and we are yet far off from that goal. But the time has come for an approximation being attempted. And the first necessity is the discipline of brotherhood, the organisation of brotherhood; for without the spirit and habit of fraternity neither liberty nor equality can be maintained for more than a short season. The French were ignorant of this practical principle; they made liberty the basis, brotherhood the superstructure, founding the triangle upon its apex ...... the triangle has to be reversed before it can stand permanently." (Ref.3)

Sri Aurobindo was convinced that, once given her freedom, India would develop in herself the means to reverse the triangle.

Inevitably, Sri Aurobindo's political activities and those of his associates brought him into conflict with the British in India . He was arrested on charges of sedition in 1908 and spent a year in the grim conditions of the jail at Alipore. It was a time of great significance in his life. He realised more vividly than ever before the one spirit that unites and moves mankind, and it changed his perception of the role that the political struggle had played in his life. It no longer seemed an end in itself, but only the beginning of his work to hasten the advent of a new consciousness in mankind based on the acceptance of human unity as a fact. His experiences while in prison convinced him of the truth long preserved in the ancient spiritual traditions of India . "The only result of the wrath of the British Government, he wrote was that I found God." (Ref. 4)

Sri Aurobindo saw that a sense of the infinite pervading all things, even the most material, is native to the Indian soul: that sense is what makes true brotherhood possible. In the Human Cycle he wrote:

"Yet is brotherhood the real key to the triple gospel of the idea of humanity. The union of liberty and equality can only be achieved by the power of human brotherhood and it cannot be founded on anything else. But brotherhood exists only in the soul and by the soul: it can exist by nothing else. For this brotherhood is not a matter either of physical kinship or of vital association or of intellectual agreement. When the soul claims freedom, it is the freedom of its self-development, the self-development of the Divine in man and in all his being.

When it claims equality, what it is claiming is that freedom equally for all and the recognition of the same soul, the same godhead, in all human beings.

When it strives for brotherhood, it is founding that equal freedom of self -development on a common aim, a common life, a unity of mind and feeling founded upon the recognition of this inner spiritual unity.

These three things are in fact the nature of the soul; for Freedom, Equality, Unity are the eternal aspects of the Spirit. It is the practical recognition of this truth, it is the awakening of the soul in man and the attempt to get him to live from his soul, and not from his ego, which is the inner meaning of religion, and it is that to which the religion of humanity must also arrive before it can fulfil itself in the life of the race."(Ref. 5)

After his release from Alipore, Sri Aurobindo returned to the political arena. He started an English language weekly paper, The Karmayogin and a Bengali weekly, he spoke at nationalist meetings and challenged the moderate faction for their lack of firmness. At this time he began to be known in British circles as the most dangerous man in India . There was a real possibility that he would be arrested again. Being forewarned, Sri Aurobindo left British India and took refuge first in Chandernagore, and then in Pondicherry .

Sri Aurobindo arrived in Pondicherry on April 4th 1910. He would remain there for the rest of his life, working out the vast synthesis of intellectual knowledge and spiritual experience that he called Integral Yoga. All the knowledge he had amassed during his explorations of Western and Indian philosophy, culture and tradition, was poured out into a series of studies published in serial form in a new journal called the Arya. It was an achievement without precedent, more than thirty volumes of philosophy, yoga, history, social and political studies, translations and commentaries on ancient texts, literary criticism, poetry, plays – a complete and integrated system of thought and knowledge that pointed to something beyond itself: the discoveries of the future. He had already prepared the ground for the independence of India . He had laid the sure foundation, now others would continue to build on it. His own work for human progress would no longer be on the surface for all to see.

The last 24 years of Sri Aurobindo's life were spent in seclusion, but that did not mean a withdrawal from life. He kept before him the ideal of freedom and knew from experience that true freedom has to discovered within the human heart, has to flower into the acceptance of ‘the other' as brother or sister, not just in theory but in fact. His final definition of freedom is a vision that transcends rational thought and leaps up towards an almost mystical insight:

"Freedom is the law of being in its illimitable unity, secret master of all Nature: servitude is the law of love in the being voluntarily giving itself to serve the play of its other selves in the multiplicity. (Ref. 6)

It is when freedom works in chains and servitude becomes a law of Force, not of Love, that the true nature of things is distorted and a falsehood governs the soul's dealings with existence.(Ref. 7)

Nature starts with this distortion and plays with all the combinations to which it can lead before she will allow it to be righted. Afterwards, she gathers up all the essence of these combinations into a new and rich harmony of love and freedom.(Ref. 8)

Freedom comes by a unity without limits; for that is our real being. We may gain the essence of this unity in ourselves; we may realise the play of it in oneness with all others. The double experience is the complete intention of the soul in Nature.(Ref.9)

Having realised infinite unity in ourselves, then to give ourselves to the world is utter freedom and absolute empire. (Ref. 10)

Infinite, we are free from death; for life then becomes a play of our immortal existence. We are free from weakness, for we are the whole sea enjoying the myriad shock of its waves. We are free from grief and pain for we learn how to harmonise our being with all that touches it and to find in all things action and reaction of the delight of existence. We are free from limitation, for the body becomes a plaything of the infinite mind and learns to obey the will of the immortal soul. We are free from the fever of the nervous mind and the heart, yet are not bound to immobility. (Ref. 11)

Immortality, unity and freedom are in ourselves and await there our discovery; but for the joy of love God in us will still remain the many. (Ref.12)"

This was Sri Aurobindo's last word on the nature of freedom.

Sonia Dyne

References:

1) Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo - CWSA, Vol.36, p.478

2) CWSA, Vol. 2, Collected Poems, p.17

3) Ref. 3 - CWSA, Vol. 1, Early Cultural Writings, p. 530

4) Sri Aurobindo - Tales of Prison Life, p.3

5) CWSA, Vol.25, The Human Cycle, p. 570

6) CWSA Vol. 13, Essays in Philosophy and Yoga, Thoughts and Aphorisms, p. 206

7) Ibid

8) Ibid

9) Ibid

10) Ibid

11) Ibid

12) Ibid

References kindly furnished by Aryadeep

See Also